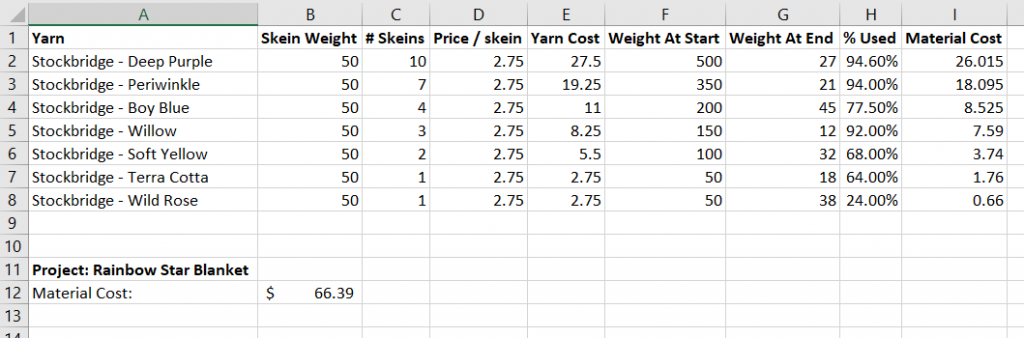

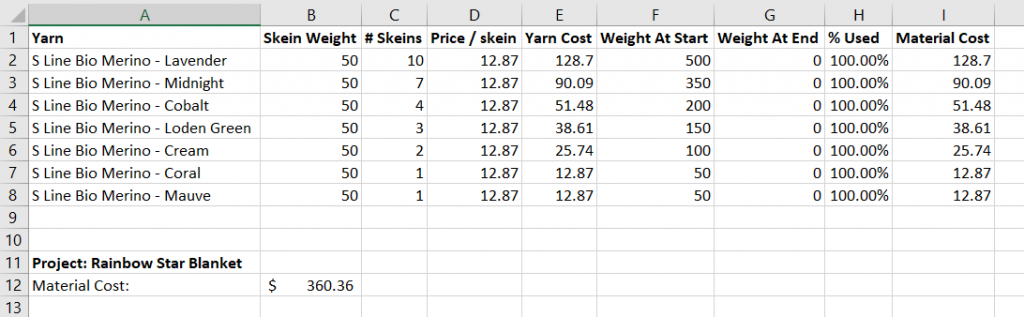

Tax accounting doesn’t require you to track per-item cost of materials. Money for inventory on a shelf v/s money for inventory used in products – same diff. But if you want to know how much you are profiting for each sale, it helps to track the cost of goods per item.

Soap is fairly easy because there’s a recipe — you know how much of a certain oil you’ve used in the end product because you weighted it out to the nearest tenth gram to start with. You still have to know how much you paid for that oil (well, close enough – prices change and I’m not interested in the level of accuracy which would require knowing from *which* order the oil I’m using *this* time came). But did you pay shipping and/or tax? If not, then the cost per gram is simply the price you paid divided by the number of grams purchased. If you *did* pay shipping or tax — then you need to calculate each item as a percentage of the order. You can do this just as a percentage of the total order cost ($ for item / $ for total order) and use that for both tax (accurate) and shipping (accurate if shipping is assessed by order value, probably close enough if shipping is assessed by weight). Or you can calculate the percentage of total order cost and the percentage of order weight (item weight / sum of weight of all items ordered). Use the order cost % for for tax calculations and the order weight % for shipping calculations. Then multiply tax and shipping charges by their respective % values.

A 35# pail of coconut oil for 43.78$ with no shipping but 3.28$ in tax as the only item ordered = 47.06$. 35# is 560 ounces (I trust the supplier’s scale here). Which is 0.084 cents per ounce. My 20% superfat coconut oil soap recipe uses 66 ounces. That’s 5.54$ of coconut oil.

Lye cost is a more complex calculation because I order it along with other specialty items. It was 50$ for the whole order of lye. The lye was 85% of the previous order’s weight. Shipping was 17.79. So the lye’s portion of the shipping was 0.85 * 17.79 = 15.12$. The lye was 61% of the order’s value. Tax was 6.19. The lye’s portion of tax was 0.61 * 6.19 = 3.78$. The sum of these (50+15.12+3.78) is 68.9. Each container is 27 ounces of lye and I got 5 containers — 27 * 5 is 135 ounces. Divide the lye cost by ounces received, 68.9/135, and I paid 0.51$ per ounce of lye. There are 9.6 ounces of lye in my recipe, which adds 4.90$ for lye.

Lavender essential oil was 33.54$ for 16.6 ounces. 16.07$ shipping, and the EO was 7% of the order weight. That’s another 1.12$ for shipping. Total cost for the EO is 34.66. Divide by ounces and it is 2.03$ per ounce. I used 4 ounces of the EO – 8.37$

The lavender scented, uncoloured batch of my coconut oil soap costs 5.54 + 4.90 + 8.37 = 18.82$ to produce. Now this is a 6# batch of soap, 24 3-oz bars. To calculate a per-bar cost, divide the total batch cost by the number of bars cut. 18.82 / 24 = 0.78$.

This is the sort of thing databases and spreadsheets are really good at doing. It’s the same formula over and over again. There are specialty accounting packages specifically for individual craft segments (i.e. a single piece of software that tracks inventory and unit cost thereof, recipes, sales and unit costs thereof and can analyze the data all sorts of ways). 100$ for the software, which is deductible against business income – it’s an investment in the business and saving yourself time. But for an initial foray into marketing a product, a simple spreadsheet will do. SoapCostCalculator is a spreadsheet I built to get an idea of how much each bar of soap was costing me.